Although I rail against the damage I believe the Internet and especially social media has done to our civil discourse, I must admit that I get wonderful surprises on a pretty regular basis when people track me down through my website. The most recent treat came from a fellow whose family lived in a Maryland farmhouse in the years before my parents bought it in 1950. For nineteen years, our family spent many weekends and much of the summer at the place my father dubbed “Polecat Park” after the skunks we had to evict from under the front porch. I was surprised to learn from this correspondent that Polecat was a fine example of a Greek Revival farmhouse as we always considered it to be a rundown old place whose charm lay less in the quality of its architecture and more in the freedom it gave us city children.

For example, in Washington, we children were not allowed to wear sneakers in the living room as we might rip up the ancient Aubusson rug my father had purchased in France. We ate in a separate dining room so my parents could be sure that the formal dining room remained clear of toys and discarded games for important political guests. And we could never make noise in the hallway outside my father’s office for fear of disturbing him in the middle of writing one of his thrice weekly newspaper columns.

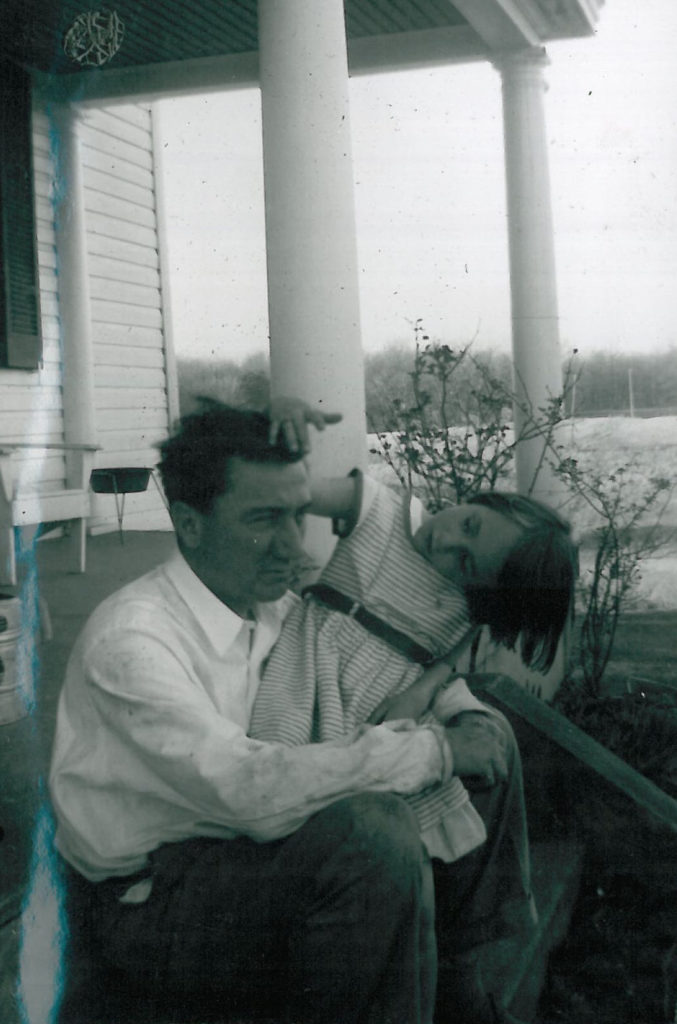

At Polecat, the wallpaper in the living room might be peeling in the corners and all the kitchen drawers stuck sliding in and out and the back porch tilted at a certain rakish angle, but nobody cared. We had much more access to my father who taught us how to shoot a .22 rifle and kill a bass hooked in the murky pond by snapping its neck.

We could roam freely through the adjacent fields, explore the various levels of the old barn where the neighboring farmer stored his hay and throw ourselves off a rickety raft into the pond without bothering whether an adult was watching or not. Since they didn’t seem to worry, we didn’t either.

At Polecat, as Daddy wrote in a 1956 article for the Saturday Evening Post entitled “Why Do I Keep the Damned Place,” we “rediscovered the joys of squalor, the pleasures of being grubby.”

In that same article, he described the house as an “oddly shaped termite feast” and “a rural slum dwelling.” My parents’ chic friends had much fancier houses in fancier locales like the Eastern Shore, but to their credit, my mother and father didn’t care what their friends thought as long as they kept turning up for Sunday lunches — which they did. In photographs from those years, Washington journalists, diplomats and CIA operatives are draped over chairs on the front porch or sprawled on the lawn digesting the delicious lunch my mother managed to produce in the squalid kitchen, a feast that was always accompanied by many bottles of wine.

My parents had a laissez-faire attitude towards their houses: if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it and if it is, try to ignore it. As Daddy wrote, “It is remarkable how much money you can save and how much physical effort you can avoid, once you learn how to rise above dirt and disorder.”

For us children, Polecat was heaven and remained so for me, until one summer afternoon at the age of twelve, I discovered a black snake curled in the toilet of the upstairs bathroom as I was about to lower myself. I pulled up my shorts and screamed for my father. We were used to the snakes outside. They slid around in the fields and the barn and under the porch. Even though Daddy argued that they kept down the mice population, my mother insisted he shoot them which he did with his .22 rifle. Once he pronounced the snake dead, my father would empty the gun of ammunition and hand it over to whichever of his children had won the contest to carry the black body to the dump. It was a job that required skill because long after they are dead, snakes keep jerking and shuddering as if their bodies are trying to restart themselves. With no warning, the thick black rope might suddenly begin to twitch and if you weren’t careful or even if you were, that dead snake would manage to shake itself right off the gun and you’d have to scoop it up again and continue your parade to the dump with all the children on the place following behind.

Snakes outside were scary but tolerable. However, a snake seeking the cool of the toilet inside the house was too much. After that traumatic experience, as often as possible, I invited myself to friends’ houses for the weekends.

I was delighted to learn from my website correspondent that the current occupants of the house are committed to restoring it under a farsighted curatorship program run by the state of Maryland. Curators who take on one of these old houses have “the right to lifetime tenancy in an historic property in exchange for restoring it, maintaining it in good condition, and periodically sharing it with the public.” Recently, the family who have embarked on this ambitious project, sent me pictures of their children hurtling down a homemade water slide they fashioned on the front lawn. It makes me so happy to know that Polecat is being lovingly restored to its original grandeur, but even more so that the house and the land are giving another generation of children the kind of country escape that my brothers and I remember so vividly and with such affection.

Really interesting about the curatorship. And I wish I could develop your father’s attitude when it comes to the renovations needed here!! Great piece, thanks Elizabeth

Thank you, Meg. This one was fun to write.