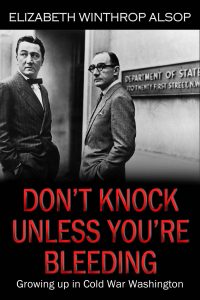

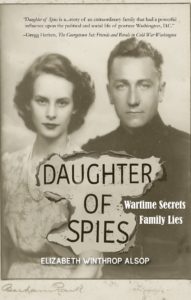

In the early days of writing Daughter of Spies, my memoir that will be published in the fall, I was convinced that I could write equally about both my parents, but as I detailed in another blog post, the writer William Zinsser proved me wrong. When he told me that I had to choose one of my parents as the focus of my story, I didn’t believe him. But in the end, I chose my mother and much of the fascinating bits and pieces I’d unearthed about my father’s childhood, his checkered college career as well as his war history had to end up on the cutting room floor.

The books written about my father detail his travels, his columns, and the stories he broke. But in writing the memoir, I didn’t focus on my father’s interview subjects or the political intrigues of cold war Washington. I was much more interested in the emotional landscape of our family. However I did briefly consider following in his journalistic footsteps, and so spent one college summer interning with the Berkshire Eagle in western Massachusetts.

I replaced the reporters who went on vacation, so I filled in as court reporter one week, obituary writer the next, society columnist the third and so on. In addition, I was encouraged to submit articles for Berkshire Week, the newspaper’s weekend insert.

For the most part, it was a job I really enjoyed and at the end of the summer, I knew it was a career I didn’t want. I came away eager to return to my fiction writing, believing incorrectly, that if I created characters from my imagination, I would have more control over them than over people whose stories ended up, for good or bad, in the newspaper. Once again, I was wrong. The more you try to control fictional characters, the more quickly your story dies on the page.

I learned many lessons about writing from my father from using the simplest language to relying on concrete details and active verbs in my descriptions, but I think the most important takeaway was the need for meticulous, detailed research. Although others referred to him as a journalist or a columnist, he always called himself a reporter. No wonder the title he and his older brother, Joe, chose for their weekly newspaper column was Matter of Fact.

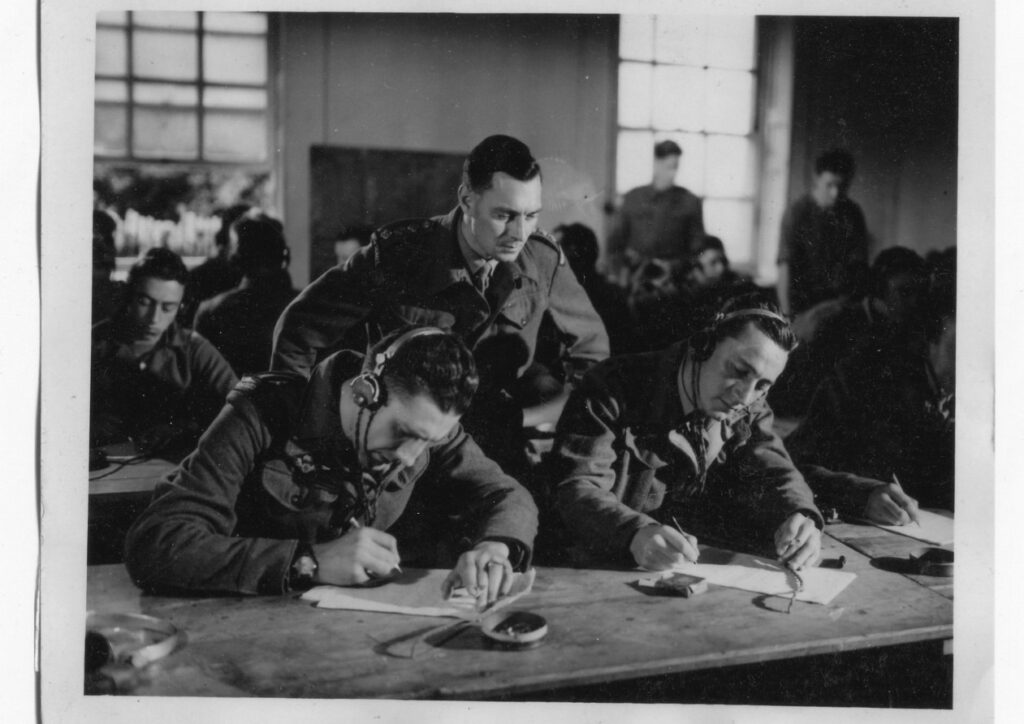

Saturday Evening Post, September 1962. Used with permission

He would spend weeks and sometimes months preparing for a trip abroad or polling Americans about their lives and their concerns or traveling widely to understand on a deeper level his interview subjects and their backgrounds. He took notes in small spiral-bound pads which he kept all over the house. Much of his research never ended up in the articles he wrote, but what he’d learned always informed the piece.

In writing fiction, I use research in the same way. Know everything you can about your subject so that when you bring your characters onstage, the reader will sense the depth and bulk of the iceberg, even when you only give them the tip.