Remembrance Sunday is always observed in England and the Commonwealth on the Sunday nearest to November 11th, Armistice Day. The First World War officially ended in 1918 on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.

This year we were in the U.K. for that weekend, and when I bought a paper poppy at Paddington Station to clip onto my lapel, I remembered a picture of my grandmother selling poppies from a basket on the streets of London in 1919. She’s the one on the left.

We decided to attend the Remembrance Sunday services at Christ Church, Kensington, a lovely small stone church directly across the street from our rented flat.

As I sat in the pew listening to the young female trumpeter playing Reveille, I thought of all the members of my family who had served England in the two world wars. My great uncle, Charles Edward de La Pasture, died at Ypres on October 29, 1914, only six months after he’d married my great aunt.

Another great uncle, Wilfred Mosley, a captain in the 1st Wiltshire Regiment, survived some of the worst battles of the First World War and served in the Home Guard in World War II.

My uncle Ian, my mother’s only sibling, was killed on August 31, 1942 in the battle of Alam Halfa in the western desert. He was 20 years old.

He is buried in the British military cemetery at El Alamein.

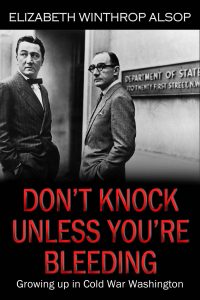

was rejected by the American Army and enlisted in the Kings Royal Rifle Corps. He fought in Italy in 1943, then joined the O.S.S. and dropped into France behind enemy lines in the summer of 1944. His brother, John, who also trained in northern England and Scotland, parachuted into France the month before my father to join Nancy Wake’s team working with the French Resistance.

But as the congregation rose to sing GOD SAVE THE QUEEN, I wasn’t thinking about the soldiers who went to war, but about the women in my family. My mother was fourteen years old when she was evacuated from Gibraltar, seventeen when she went to work for MI5 as a decoding agent, eighteen when she married my father and crossed the North Atlantic, pregnant and alone. But it was even worse for my grandmother who lost everybody.

Her son was killed, her daughter moved to America, and two years later, her husband left her for his secretary with whom he’d been carrying on a secret affair throughout the war. Granny’s only choice was to close down her life in Kent, England and move back to Gibraltar to live with her mother and sister.

War destroys more than the soldiers who are sent to fight on the front lines. It blows whole families apart and sometimes, it takes generations to put them back together again.

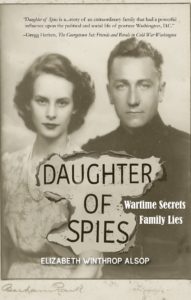

#wwiimemoirs, #wwibiographies, #memoirs_of_wwii, #daughterofspies, #elizabethwinthrop, #elizabethwinthropalsop, #wartimesecrets

So much loss, so much trauma. And bravery and guts, stamina, keeping on going. What else to do? Honor them with your writing, enfold them into your identity and purpose, etc. Very moving!

As a British person, I found this very moving. My father served in Bomber Command in WW2. This was dangerous and thus only took volunteers such as himself. I believe half of Bomber Command did not return and 1 in 10 ended up as POW’s, Dad included. It had an enduring and profound effect on him. My generation has been so much more fortunate. Dad also had a cousin who was lost at sea during the war. As for WW1, I have no family history. But I do agree that the women at home suffered too, such as my Aunty, by marriage, who was kicked out of home for conceiving when Uncle was on shore leave, and so lived with my family for the rest of the war, with my lovely cousin. Uncle came home when my cousin was seven. My cousin said ‘who is he?’ And cried.