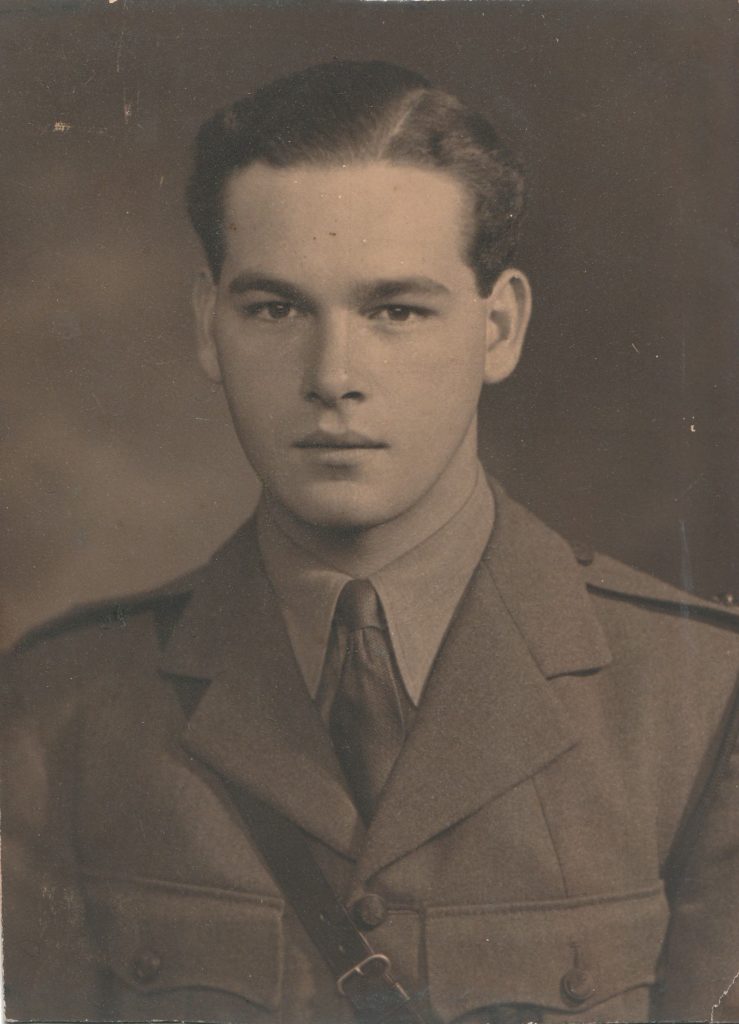

Born Gibraltar November 20, 1921

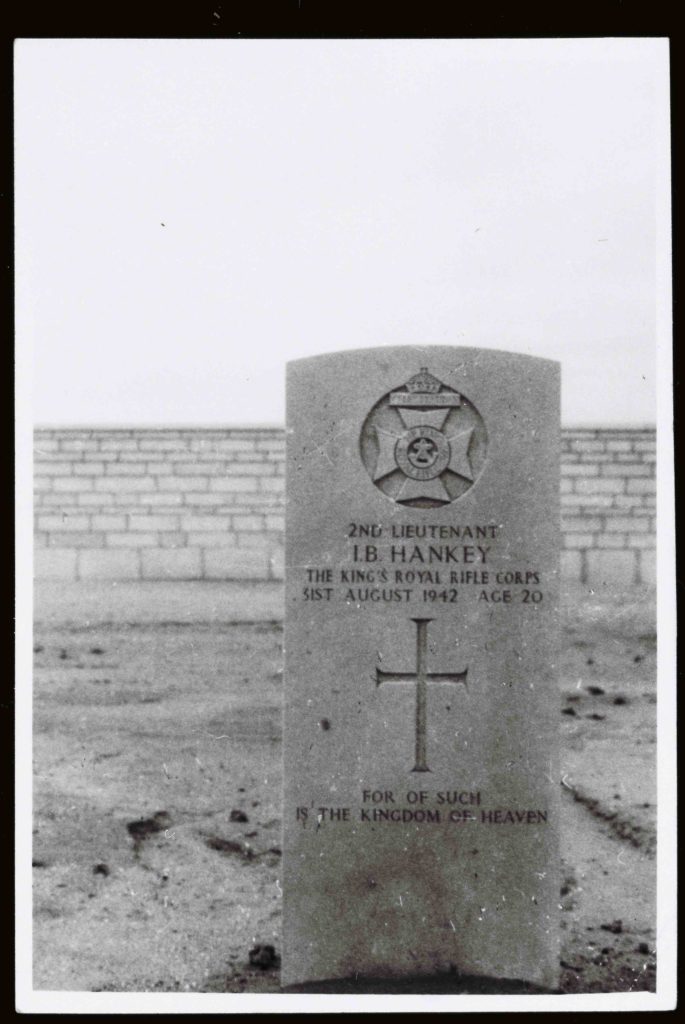

Died in Libya, Battle of Alam Halfa, August 31, 1942

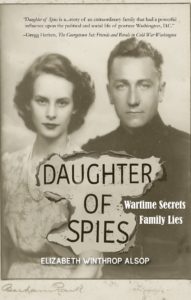

When many years ago, I started writing what would turn into my upcoming memoir, Daughter of Spies: Wartime Secrets, Family Lies, I met with the well-known journalist and author, William Zinsserto discuss with him the book I had in mind. He listened attentively and then quietly dropped a bomb. “You know,” he said, “you can’t write about both of your parents in the same book. You have to choose one.” I left the room vowing to prove him wrong and two years later, after months of rejected drafts, I finally acknowledged that he was right. This had to be a book about my mother and my relationship with her. That left many beloved scenes and characters on the “cutting room floor.” One of those was my mother’s older brother, Ian Barnard Hankey, a man I would never meet because he was killed in Libya in the Second World War.

One day when I was visiting my mother in her declining years, she handed me a manila envelope. On the outside, scribbled in pencil, a note read “Uncle Ian’s Effects.” For a writer researching family history, this felt like a key to a door locked long ago. I scurried back to my room and tucked this treasure into my suitcase before my mother could change her mind. Lately she’d begun to object to me taking the bits and pieces of her life out of the house for fear that, like her memory, they would disappear forever.

Ian is four years older than my mother and in the upper class British tradition, when he is eight years old, he is sent from Gibraltar to Gilling Castle, a boarding school in England.

From there, he goes to Ampleforth College, a premier Catholic school in Yorkshire and on the way back to school his senior year, he hops off the train in Birmingham and with two of his cousins, he enlists in the army. None of them admit what they’d done to their parents.

In May of 1940, all civilians are evacuated from Gibraltar so that it can be turned into a military. base. Ian, my mother, and my grandmother board the S.S. Ormonde. As they always do on these crossings, the two siblings teach the younger children how to feed left-over breakfast toast to the seagulls hovering above, squabbling with one another like the children in line below. Ian might look like a child, but less than a week after their evacuation ship docks in London, he is assigned to the Initial Training Corps, Worcestershire Regiment as a rifleman. He is nineteen years old.

In the envelope my mother handed to me, I find the letters Ian wrote home to England from his deployment in the western desert as they called that theater of war. I decide to transcribe them, and I wince as he constantly reassures his parents that despite the danger of the war in the desert and his stepping accidentally on an Italian mine and various other fevers, torments of the weather and the flies, he’s really fine. Every piece of paper I pick up, open, type over and put on the bottom of the pile brings me closer to the last one.

Ian doesn’t know of course, that in the next century, his niece will be reading these missives, but he’s always conscious of the censor looking over his shoulder. Most of the letters are filled with trivial details, questions about people at home, sentences like “many things have happened since I last wrote none of which I can relate I am afraid. Anyhow I am safe and well, although I have lost weight considerably.”

The last letter is written August 26, 1942, five days before he is dive bombed by a German Stuka while attacking a tank patrol. He writes of another glorious sunrise, of the constant flies and a detailed description of a bird. “I saw the most lovely bird yesterday; I was told it was a desert jay; brilliant green body and wings tipped with black and backed with a very light brown. The flight was similar to that of a green plover.” And he ends with this plea: “Remember what I said about the silk stockings or anything else you need; which I can (sic) these people in Cairo to send you.. They are simply dying to (be) able to do something for me.”

The people in Cairo were “dying” to do something for him. In five days, he would be dying too, but not for a pair of silk stockings.

The telegram that announces his death arrives twelve days later from the Under Secretary of War.

I always assumed it was a soldier who had to deliver this kind of news, but there is a note at the top of the envelope indicating that it passed through the Knightsbridge post office so maybe it is just some errand boy who rests his bike against the front railing of the building and bounds up the steps. But how could that be? How could the British government allow news that will change lives forever to be delivered by a boy on a bicycle?

I imagine it is my grandmother who opens the door. Her husband is at his office at the Ministry of Economic Warfare, and her daughter, Patricia, enrolled in the Carr Saunders School in the Cotswolds, is taking nine months of secretarial courses to prepare for war work.

The message is typed, all in CAPITALS, on glued strips of paper, the way all telegrams looked back then.

DEEPLY REGRET TO INFORM YOU OF REPORT RECEIVED FROM MIDDLE EAST THAT 2ND LT I B HANKEY THE KINGS ROYAL RIFLE CORPS WAS KILLED IN ACTION ON 31 ST AUGUST 1942 THE ARMY COUNCIL DESIRE TO OFFER YOU THEIR SINCERE SYMPATHY.

On that exact same day, a world away in a baronial castle in northern England, Ian’s younger sister Patricia met the man she would marry, a 28-year-old American who was also serving in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps. I have this strangely romantic image of my uncle, as he was floating out of the world, pushing my father into my mother’s path to make sure she was taken care of since he wouldn’t be there to do it.

Uncle Ian would have been 100 years old this month.