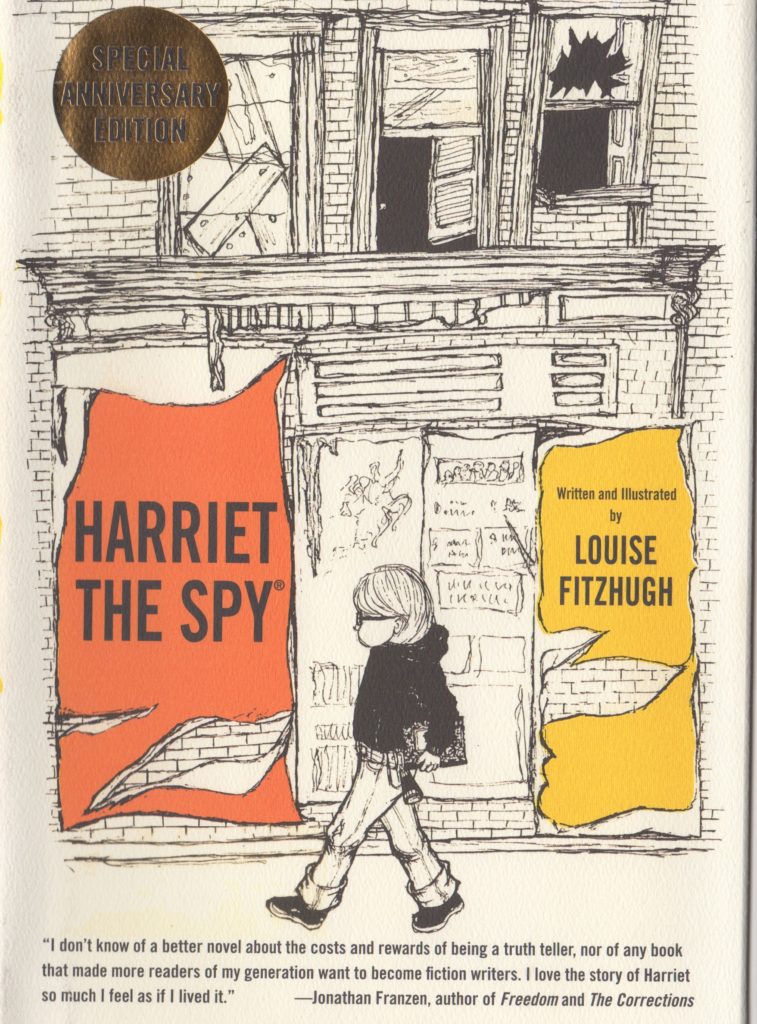

Every reader can look back and remember the special books they read as children. I’m the same. For me, it was the books my British mother introduced into our home library. They ranged from Enid Blyton’s Castle of Adventure (and the other seven in that series) down to Dr. Doolittle, The Borrowers in all their settings, Winnie the Pooh and Alice in Wonderland. But as a fiction writer, the books I looked for in my later years were the ones that not only inspired me but also warned me about the loneliness and the pitfalls of the creative path. First among these was Harriet the Spy so I was grateful to be invited to write an essay for the 50th Anniversary edition of this seminal novel. Here’s what I said.

I didn’t read Harriet the Spy until I was trying to land a job as an editorial assistant in the children’s book department at Harper and Row. I read my way through every novel they’d published in the previous twenty years. Harriet was at the top of the list.

I recognized my kinship to Harriet the moment she told Sport in the first chapter that she has to take notes on the people in the subway because she’s seen them and she wants to remember them. How did Louise Fitzhugh know me so well? The answer, of course, is simple: she was a writer. All writers are spies, going about the very important task of gathering their material, and when they’re on the job, they’re unsentimental, focused, indefatigable. “Spies don’t go with friends,” Harriet tells Sport. The life of a spy is a lonely one. I was the only girl in a family of six. I knew about being different, being on the outside looking in. Writing things down in my journal was my way of making sense of the world, from the confusing behavior of my parents to the cruelty of certain people who called themselves my friends to the irritating torments of my brothers. My journal was the one place where I could be completely honest about my feelings.

I was more careful than Harriet. I never took my spy books out of their secret, locked place in my bedroom, so fortunately, I didn’t lose any friends over what I wrote there. However, as my notes grew into published stories, a few family members began to have their misgivings. Soon after my second novel came out, one uncle warned that “every time Elizabeth writes a book, it’s like dodging a bullet.”

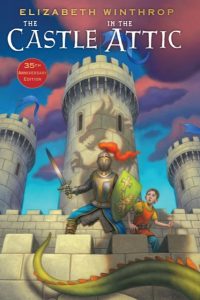

But I connected with Harriet in other ways. I realize now that when I came to write my fantasy novel, The Castle in the Attic, fourteen years after I’d read Harriet the Spy, I was channeling a version of Harriet’s nanny, Ole Golly. Harriet is devastated by Ole Golly’s departure. My character, William, feels equally desperate when he learns that his nanny, Mrs. Phillips, is moving back to England. Harriet works through her feelings in her notebook. William resorts to magic, but their motivation is the same: Hang on to the one person who loves you despite all your faults. Do anything to keep her, and if she leaves you, do anything to bring her back, no matter the consequences.

Although I never had a nanny like Ole Golly or Mrs. Phillips, I grew up in a house with a cook named Jessie Mae Jefferson Tucker. Early on, Jessie and I made a secret deal. She owned the only television in the house, and she let me watch women’s wrestling in her third-floor bedroom, as long as I didn’t tell anybody that she often went out herself after my parents had left for dinner parties. I was eleven, Harriet’s age. My older brothers had been sent to boarding school, and even though it was scary to be left in charge of the younger ones, I was committed to our secret pact. Jessie got to go out on her dates, and I got to watch powerful, muscled women wrestle each other to the mat. Jessie and I inhabited our own closed world the way Ole Golly and Harriet do. Children and staff members can feel equally powerless over the people who rule their lives, whether they be parents or employers, so it’s no surprise that they form clandestine liaisons. Children do a lot of their growing up in the kitchen and in top-floor bedrooms, the places in a house that parents like Harriet’s and mine rarely invade and know little about.

Not unlike Harriet’s friend Janie Gibbs, who cheerfully mixes potions in her bedroom and makes dire threats against all adults, my oldest brother Joe, loved blowing things up in a lab he’d set up in our basement. One time, he got too close to his own explosive mixture and had to be taken to the hospital. When Joe decided it wasn’t feasible to blow up his hated boarding school, he wired the headmaster’s office instead, so he could tape the faculty meetings. He was eventually discovered and expelled, but we younger siblings, sworn to secrecy, never betrayed him.

Joe always gave us hope that in the battle between children and adults, we might actually triumph. We six were all spies, but I was the Harriet in my family, the one who took the notes and turned them into stories.

Readers don’t have to live the exact life that Harriet does in order to understand what her story is telling us. Writers will recognize themselves just as easily when they read Harriet’s story today as they did fifty years ago when the book was first published. Even though readers today may be recording their findings on an electronic tablet or publishing their observations on social media sites, the hard truths that Harriet learns as she goes from a spy taking notes to a writer writing stories remain the same.

If you want to be a writer, write down everything. Find out all you can, because life is hard enough even if you know a lot. Put down the truth in your notebooks, but don’t use it against your friends.

And as Ole Golly tells Harriet, gone is gone. Don’t try to hold on to people or lie down in your memories. Make stories from them.

You can find the 50th Anniversary edition of Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh at your independent bookstore through Bookshop.org or on Amazon. You might also be interested in a new biography of Louise Fitzhugh: Sometimes You Have to Lie: The Life and Times of Louise Fitzhugh, Renegade Author of Harriet the Spy by Leslie Brody.

ELIZABETH WINTHROP ALSOP is the author of over sixty works of fiction for all ages.

The daughter of the journalist, Stewart Alsop and a great grand-niece of Theodore Roosevelt, Elizabeth was born with a silver spoon in her mouth which has always been combined with a healthy dose of skepticism about life in America’s WASP society. She has recently finished a memoir entitled Daughter of Spies: Wartime Secrets, Family Lies about her parents’ love affair in England during the war and the complications of their marriage in the politically charged atmosphere of 1950s Washington.

Her previous short memoir, Don’t Knock Unless You’re Bleeding: Growing up in Cold War Washington, is available as a Kindle single.

Coming from Regal House Fall 2022, Daughter of Spies: Wartime Secrets, Family Lies

#kidsbooks, #childrensbooks, #kidlit, #booksforkids, #reading, #kidlitart, #raisingreaders, #kidslit, #booklover, #raiseareader, #childrensliterature, #book, #kidsbookswelove

#elizabethwinthrop, #elizabethwinthropalsop, #memoirs, #daughterofspies