Winslow Press, 2001

Winslow Press, 2001

In the early 1930’s, the Great Depression touched every corner of the country. One quarter of the workers in America didn’t have jobs. Banks in thirty-eight states had closed their doors, and many others were about to collapse.

Imagine a girl named Emma Bartoletti who lived in a Massachusetts mill town. Imagine that Emma wrote to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and that the president wrote back.

Buy the book now: |

September 13, 1933

North Adams, Massachusetts

Dear Mr. President Roosevelt,

Last week, my father was making $20 a week and now he only gonna be making $14. He says you are President and you know best, but I’m not so sure about that. So please explain to me what you are thinking.

Your friend,

Emma Bartoletti

Dear Miss Emma Bartoletti,

October 14, 1933

The White House

I’m wondering if you have a radio, and whether you are able to listen to my fireside chats. At the end of July, I gave the country a talk on what the NRA is supposed to do and how important it is for the general prosperity of our whole country…I appreciate hearing from you and ask that you keep in touch and let me know more about your family and your situation. Down here in Washington, where everybody talks and nobody listens, it is refreshing to hear a clear voice from New England.

Very sincerely yours, Franklin D. Roosevelt

Elizabeth Winthrop talks about the creative process:

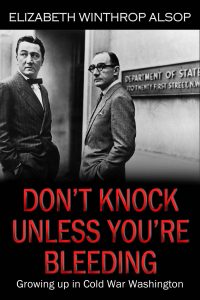

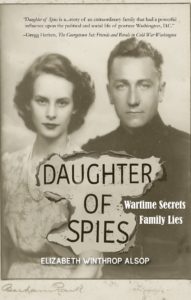

Corinne Alsop (author’s grandmother) and first cousin Eleanor Roosevelt when Eleanor was first lady.

When the editor at Winslow Press approached me about writing the volume on Franklin Delano Roosevelt for their DEAR MR. PRESIDENT Series, I was enthusiastic about the project for many reasons. First, in a distant way, I happen to be related to FDR. My grandmother Corinne Robinson Alsop was Eleanor Roosevelt’s first cousin. For years around the dinner table, I had heard tales of my grandmother’s times with her uncle Theodore and her pack of Roosevelt cousins. I knew that although Grandmother was a staunch member of the Republican party, she had remained good friends with Eleanor and bantered with her cousin Franklin whenever they met. In my back hallway, I have a framed letter written to my father in the army from Cousin Eleanor on the occasion of his marriage to a young English bride. It reads: “I was so happy to hear from your mother that you are married to a very charming young lady. I want to send my very best wishes to your wife and my congratulations to you. I shall look forward to meeting her and to seeing you when you get home. Affectionately, Eleanor Roosevelt.” Under that in her spidery handwriting she added, ” Cousin Franklin joins me in good wishes.” In some ways because of all this family history, it was easier for me to write letters in Cousin Franklin’s voice than in twelve year old Emma Bartoletti’s.

But there were other reasons for my enthusiasm. I have always admired FDR’s energy and his determination to fight for the forgotten people of America during one of the darkest periods of our country’s history. I was impressed by his courage in facing polio. And I loved his optimism in the face of daunting challenges.

I told the editor from the beginning that I wanted to set the book in a mill town in New England. First, I believed that the Depression in the Dust Bowl, in the South and in the West had been covered by writers in myriad, creative ways. The Northeast suffered less obviously during the Thirties, but people there were out of work, out of food and running out of hope. Secondly, I had recently bought a home near the town of North Adams, Massachusetts and had become fascinated by its people and its varied history. What better way to come to know my new environs than to set a book in a mill town where the Depression affected the citizens in many different ways.

For the months that I spent researching this book (and this happens with every work of fiction I write) I lived in the world of the novel. Consequently, as many of my friends will tell you, for the summer of 2000 I became an instant expert on North Adams during the Depression years from 1933 until 1937.

I could tell you then how much money a man made in the Arnold Print Works for a forty hour week ($14). I could tell you about the ups and downs of the WPA (Works Project Administration) projects in town, the formation of the various CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps) companies in the Savoy Forest and which classes were taught in the camps in the afternoons.I could describe to you the plight of the family found starving near the Monroe CCC camp, the child whose ear was frozen as solid as the water on the floor of their unheated shack. I could tell you all about the textile workers who struck the Berkshire Fine Spinning Mills in Adams in September of 1934 and how the strike spread to mills in Williamstown and North Adams and how in the end, the workers got nothing.

I interviewed many of the older Italian residents in the town. They were eager to tell me their memories and they turned out to be gifted storytellers who gave me the kinds of details that bring a place and a period of history alive for a listener who wasn’t there. One woman remembered that her mother made the hoboes sit on the coal box when they came by to ask for food. Another man recited the names of all the movies he saw at the Paramount Theater. Another woman talked about the dances her aunt loved and her boyfriend who enlisted in the Civilian Conservation Corps and the times the fire department flooded the fields so the kids in town could go skating. And all of them talked about the strength of the connections in their Italian community and in North Adams in general. “People cared about each other then. We reached out to one another.” I heard those sentences over and over again.

President and Mrs. Roosevelt received five thousand letters a day during the Depression from people all over America. Some of them had to borrow the three cents it took to mail a letter. But still they wrote because they believed the President would listen. And almost all of these letters were answered.

I am proud of Emma’s story. I believe the President would have answered her letters too. As I often say to readers who ask me if my historical novels are true, I’m not saying it did happen. I’m saying it could have happened.

Winslow Press has developed a website for each of their DEAR MR. PRESIDENT Books. You can click here to find more information about North Adams, the labor movement during the Depression, the Dust Bowl, the Social Security Act as well as many more topics covered in the book.

I hope this story will give its young readers some perspective on our history. This country has suffered through tough times and has survived. And Emma was practicing her basic freedoms as a young person in a democratic society by voicing her opinions to the leader of our country. Roosevelt listened. He answered.

If you are a parent or teacher or a librarian, encourage the children you know to read about what’s happening in our country and in the world and to write to their representatives in Congress and their President to voice their opinions. It’s a great habit to start at a young age.