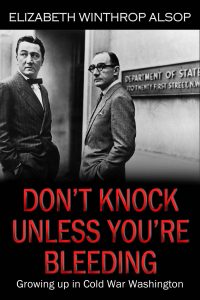

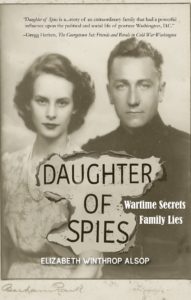

Having a famous writing father is not an easy burden when you want to be a writer yourself. It’s the reason that, until now, I’ve always written under the name Winthrop and of my 62 books, 61 are fiction. But I’m finally acknowledging that I’m the daughter of Stewart Alsop. I’ve just published an electronic book (DON’T KNOCK UNLESS YOU’RE BLEEDING: Growing Up in Cold War Washington, available on Amazon) about my childhood with two famous writing brothers. Now I’m working on a family history about my parents’ love affair in England during the war.

I call my blog roll, LOOKING OVER A WRITER’S SHOULDER, but right now, I feel my father peering over mine. I’m writing about the time he worked with the French Resistance in Occupied France from August until November of 1944. He’s mentioned this time of his life in a number of articles and most exhaustively in a memoir he wrote about dying called STAY OF EXECUTION. But the book that told the stories in greatest detail is called SUB ROSA. It was written with my godfather, Thomas Braden (who later came to be known best as the creator of the TV show “Eight is Enough” just a year after they returned from the war. SUB ROSA was commissioned by “Wild Bill” Donovan, the founder of the Office of Strategic Services, the organization responsible for training my father as a paratrooper and dropping him into France.

So here am I, sixty-eight years later, trying to reconstruct my father’s time in France from interviews and unpublished memoirs and nuggets of gold I’ve discovered on the web written by people who were there with him. But inside the book bag by my feet, I have a copy of my father’s book, SUB ROSA. Why not open it? Why not turn to that first?

On some level, I’m scared he’s a better writer than I am. And if I believe that, why bother to write this story at all? What do I have to bring to the page that he, who was there, hasn’t already said?

Nothing sabotages a writer’s self-confidence as much as comparing oneself to any relative, but particularly the father who first influenced you.

But here’s my answer for today. I now know more than my father did about the whole operation, not just his particular piece of it. I’ve seen pictures and essays written about him and about that time that he never saw. And I believe that every memoir needs a committed and interested narrator who acts as a cipher. I lost my father 37 years ago to leukemia. This is my way of getting to know him better, not just as a daughter, but as a fellow writer. Whether or not this work will engage a reader is not up to me.

First I will put the story in my words. Then I’ll take SUB ROSA out of my backpack and let Daddy speak into my ear and see where his version fits into mine.

I’m finishing a book on the Jedburghs and would love to speak with you about your father. Please respond to this email and perhaps we can collaborate on our current projects. I know Colin Beavan and my book will be more academic and concentrate more on the Jedburghs impact on the war. But the tales the Jeds told need to be in it, as much as possible and your father’s well written team report is definately in the top three of all 93 teams!

Best,

Ben